Most of it concerns Europe, US and Australia/New Zealand, but I also have a look at the numbers coming out of the established producers in Asia.

Investment amount dips, but deal count rises

Phyconomy tracked 41 investments in seaweed startups this year, slightly more than last year, and twice as much compared to 2020. However, the total disclosed amount invested dropped by almost 1/3 compared to 2021.

*Keep in mind this remains just a snapshot based on data available in the public domain. Not all equity investments disclose the amount of investment, some investments are not announced at all, and investments with debt or own means are not included.

In Europe, the amount of startups receiving funding remained high, but the cheques got smaller. Investment fell back to $34M, half of 2021 ($67M).

North America saw the opposite trend. Fewer startups raised, on average, larger rounds. Down Under, a small uptick in deals is in line with expectations as more startups are popping up.

Europe remains the place where most seaweed startups are born, although the rest of the world is also picking up the seaweed bug.

*Asian numbers mostly reflect startups outside the traditional colloids and food business.

Investments mainly went into downstream companies processing seaweeds into products, and vertically integrated growers/processors. Pure-play cultivation startups are the least popular business model, both for investors and entrepreneurs.

A limited number of applications have scooped up most of the investment since 2020: livestock methane reduction with Asparagopsis, biorefinery approaches, bioplastics and food products account for 83% of all investment tracked.

Is cultivation taking off outside of Asia?

It is difficult to find any statistics on seaweed cultivation in Europe and the US (except for Alaska – thank you!), but I managed to cobble together a graph for 4 front-runner territories in US and Europe. A promising growth curve is visible on both sides of the Atlantic.

Maine (CAGR 106%) and Alaska (CAGR 65%) had a higher growth rate than France (CAGR 28%) and Norway (CAGR 31%), which allowed them to catch up.

The obvious criticism here is that it is easy to double growth if you are starting from zero. Seaweed cultivation in Europe and North America is indeed tiny on a global scale. A more interesting question in this case is: seeing the bottlenecks in regulations, markets, cost, social license, processing and finance, will this pace of growth continue or slow down soon (or accelerate)?

You can find many pundits on the internet who are happy to share their opinion on this. It is however not always clear what these people are basing their opinion on. Instead, I thought it would be more useful to have a look at signals that point towards these different bottlenecks either opening up or becoming tighter, so readers gain more tools to make up their own mind.

Do let me know if you have positive / negative signals to add.

Will the pace of growth continue?

Regulations

Positive signals

The EU’s Algae initiative has proposed 23 actions to kickstart the algae sector in Europe. Action 2 reads: “work with Member States to facilitate access to marine space, identify optimal sites for seaweed farming and include seaweed farming and sea multi-use in maritime spatial plans.”

In the US, the SEAfood Act is set to regulate aquaculture in offshore federal waters, if it passes Congress. Also, for the first time since 1983, Washington is updating the National Aquaculture Development Plan. Three new strategic plans—for Science, Regulatory Efficiency, and Economic Development—will provide the basis for a holistic approach to expand domestic aquaculture.

Negative signals

Receiving a license for seaweed aquaculture remains exceedingly difficult and expensive in many places. In the US, outside of Alaska, it has only gotten more difficult in recent years.

Cost

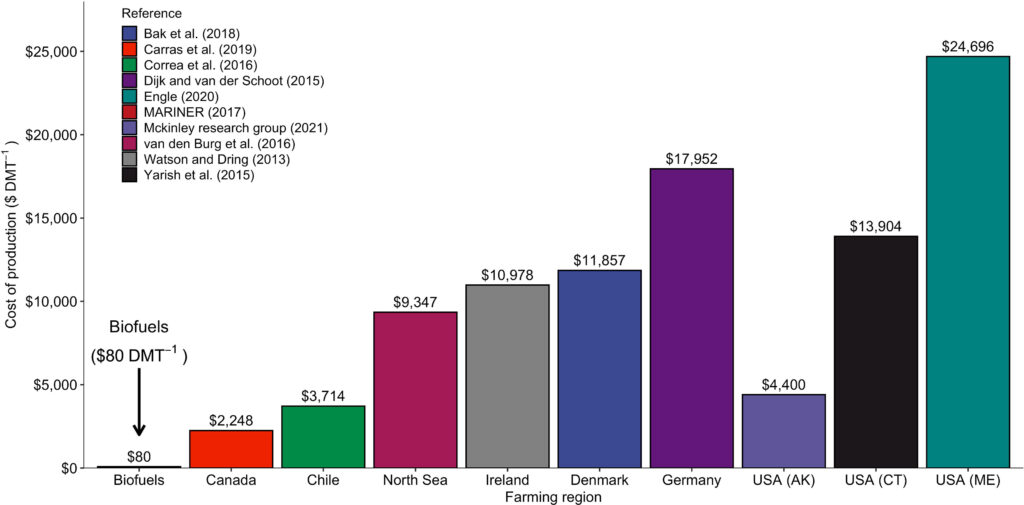

Cost remains an enormous stumbling block to scale up seaweed in new cold-water territories. Coleman et al. published research on the cost of seaweed cultivation in Europe and the Americas.

They also looked at where the most significant cost-savings could come from in the context of carbon sequestration.

Are we seeing any progress here?

Positive signals

- Innovations in breeding:

- Multi Annual Delayed Gametophytes (Hortimare)

- New bioreactors for continuous gametophyte production

- SeaCoRe bioreactor chain (low-cost, open-source)

- Industrial Plankton’s bioreactor

- Sugar Kelp Base, a 1200-sample strong kelp germplasm collection for advanced methods in kelp breeding (WHOI, UConn and Bigelow Lab)

- Innovations in cultivation

- Automated underwater seaweed seed-string deployment device (WHOI) allows farmers to seed much faster, increases seedling survivability and weather window in which seeding can occur.

- Greenwave’s Kelp Climate Fund subsidises kelp farmers

Negative signals

Profitability remains elusive for most seaweed farmers.

Markets

While the potential applications of seaweeds are manifold, the high cost of cultivated seaweeds in Europe and the US means that for now, only food and cosmetics/nutraceuticals are viable markets for seaweed farmers.

The problem here is that for personal care, the amounts needed are small, while for food applications, there is a gap between the species most in demand by food companies (Ulva, Palmaria, Porphyra), and the species that are grown by seaweed farmers (Saccharina, Alaria).

Positive signals

- breakthroughs in at-sea cultivation of

- Ulva sp.: Nordic Seafarm / Uni of Goteborg (Sweden)

- Palmaria sp.: Oceanwide (Denmark), Pure Ocean Algae (Ireland)

- Fucus sp.: Origin by Ocean (Finland), A4F (Portugal)

- Macrocystis sp.: Kelp Blue (Namibia), Ocean Rainforest (California)

- dozens of new kelp products under development

- Seaweed snack sector has grown by more than 30% in the last 12 months

Negative signals

- Europe’s fastest-growing seaweed food startup (BettaF!sh, founded 2020) only processed 4 tons of kelp in 2022

- Cultivation of Atlantic Porphyra species still faces difficulties due to the complex life cycle

Other markets

Seaweed biostimulants had a positive year with breakthrough legislation and several agchem giants getting involved.

Asparagopsis, biorefinery and bioplastics startups won grants, investments and awards and several moved to pilot production. None have made it to commercial scale yet though, so the true market test is yet to come.

2022: a busy year in seaweed carbon science

A lot of seaweed carbon science in 2022, and it looks like 2023 will continue in that vein.

Positive signals

- A rebuttal to the Gallagher paper that wrote seaweed forests could be emitters, not carbon sinks.

- Global seaweed distribution: seaweed habitats equal the Amazon rainforest in terms of both area and productivity and should be included in global C budgets.

- Urchinomics secures world first kelp restoration blue carbon credits

- Species of Fucus could remove up to 550 million tonnes of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere every year (paper – explainer)

Negative signals

- Can pumping nutrient-rich water from the deep ocean to the surface (artificial upwelling) draw down significant amounts of CO2 through micro- or macroalgae growth? No.

- A string of scientists left Running Tide in 2022

- Methane emissions offset atmospheric carbon dioxide uptake in coastal macroalgae (paper – explainer)

- What are the potential negative effects of ocean afforestation on offshore ecosystems?

- Warmer oceans may limit kelp forests’ potential to store carbon for long periods of time (explainer – paper).

- Seaweed-based climate benefits may be feasible, but targeted research and demonstrations are needed to further reduce economic and biophysical uncertainties.

New biological carbon pump research in the North Atlantic finds that for exported carbon remineralized at 1000m, which is often used as a sequestration horizon for long-term (100-1000s yrs) storage, only 66% remains sequestered for 100 years. The authors conclude that this has implications for the accuracy of future carbon sequestration estimates, which may be overstated, but also for ocean carbon dioxide removal + Blue Carbon schemes that require long-term sequestration to be successful.

Williamson and Gattuso leave even less to the imagination in their paper’s title: Carbon Removal Using Coastal Blue Carbon Ecosystems Is Uncertain and Unreliable, With Questionable Climatic Cost-Effectiveness, making it “premature to operationalize marketable blue carbon“. Therefore, while restoring blue carbon ecosystems has many environmental benefits, “restoration should be in addition to, not as a substitute for, near-total emission reductions.” Seaweed is not mentioned but many of these arguments could be said to also apply to kelp forest restoration.

Hasselström and Thomas took a critical look at seaweed LCA’s and concluded: “The sector has potential to contribute to climate change mitigation, though the evidence for this across the whole life cycle remains quite thin to date, especially relative to the hopes that are pinned upon it as a nature-based climate solution.”

Correcting the global seaweed production graph

If you have done any reading on the seaweed industry, you have come across this graph based on FAO data that shows a rapid growth of seaweed cultivation in the past 50 years.

However, independent researchers estimate the harvests for Indonesia and the Philippines 6 to 7 times less than FAO.

- Neish, I (2020) Ten success factors for the coral triangle seaweed industry

- Langford et al. (2022) Price analysis of the Indonesian carrageenan seaweed industry

- Porse & Rudolph (2017) The seaweed hydrocolloid industry: 2016 updates, requirements, and outlook

Taking their findings into account, an updated graph would something like this.

This would severely diminish the role eucheumatoids play in the global seaweed industry. That is, of course, if we can believe the numbers coming out of China and North Korea.

The same would be true for the role of Indonesia in global seaweed production (it bears repeating, if you believe the numbers coming out of China).

But even if we would disregard the inflated numbers for Indonesia and Philippines, there is another reason why the global seaweed graph is misleading. If we break it down per country and leave China and North Korea out, we see that all other major producers, with the exception of South Korea, have seen their production peak in the 2010’s (Japan as early as 1995).

Most top producing countries are in decline. These countries need new markets, climate-resilient strains and more automation to bounce back to growth.